The prospect of a swift end to the global chip shortage is looking increasingly forlorn after a leading electronics manufacturer delivered one of the gloomiest prognostics about the situation to date. Flex, a major buyer of semiconductors whose clients include some of industry’s biggest names, expects supply issues to continue for at least another year, and experts believe problems could now run into 2023.

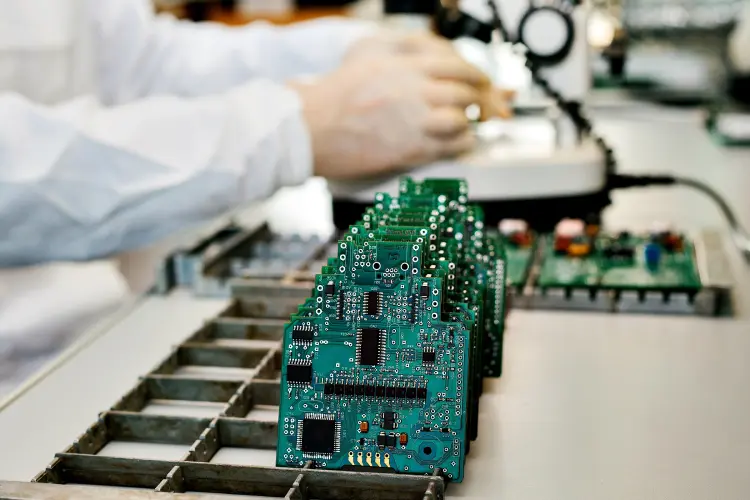

High demand for semiconductors has caused shortages around the world. (Photo by Franz12/Shutterstock)Singapore-based Flex, a contract manufacturer working with businesses including HP, Dyson and Ford, says its chip suppliers are pushing back forecasts as to when normal supply will be resumed. “With such strong demand, the expectation [to return to normal] is mid to late-2022 depending on the commodity,” the company’s chief procurement and supply chain officer, Lynn Torrel, told the FT.

It had initially been expected that the worst of the chip shortage would be over by the end of 2021, but industry analysts who spoke to Tech Monitor said many sectors should brace themselves for much longer periods of disruption.

The worst chip shortage in 30 years

Triggered by a surge in demand for electronic devices at the start of the pandemic, the chip shortage has affected a wide range of business sectors, with automotive particularly hard hit. Linley Gwennap, principal analyst at research firm the Linley Group, which covers the semiconductor market, describes the current situation as “the worst I have seen in my three-decade career” covering the sector. Figures from the Semiconductor Industry Association, the trade body for US companies working in the sector, show that chip sales in March grew 17.8% year-on-year around the world to a value of $41.5bn, with China the biggest growth market.

But while Covid-19 brought the situation to a head, Shane Rau, research vice president for computing semiconductors at IDC, says it is the result of bigger structural problems in chip supply which are taking longer to resolve than was initially anticipated. This is due in part to continuing high demand for semiconductors, particularly those used in servers that power the cloud computing boom. "The roots of the shortages are in semiconductor manufacturing capacity decisions made by the foundries and integrated device manufacturers (companies like Intel which design and manufacture chips) two to three years ago, decisions made before the pandemic of 2020 which disrupted normal demand patterns differently by chip type and system category," he says.

Will the global chip shortage continue into 2023?

As reported by Tech Monitor, countries around the world have been investing heavily in semiconductor production, with leading manufacturer TSMC pledging to build new chip foundries in Taiwan and the US, and Samsung announced a major investment in its native South Korea backed by government support. US president Joe Biden is also set to prioritise chip manufacturing as part of his Build Back Better programme, and the European Union hopes to entice more chip makers to the continent.

But while these investments are likely to eventually turn the chip shortage into a chip surplus, the benefits will not be felt for at least a year according to Malcolm Penn, founder and CEO of semiconductor industry analyst company Future Horizons. "After all the tweaks and squeezes have been exhausted, the only real answer is new capacity investment, which everyone is reluctant to do because it always triggers an inevitable over-supply and crash," Penn says. "Plus it’s expensive, both in terms of CapEx and depreciation so the return on investment is not very attractive. That said, CapEx is now starting to happen but it takes a year to build out and kick in."

Penn says a key inflection point is coming which could determine how long the crisis will last. "The pinch point to watch is Q4 2021, when demand enters its traditional seasonal slowdown," he says. "That slowdown is unlikely to be severe enough to bring supply and demand back into balance, [but] if we limp through it, shortages will persist through the first half of 2022 until the current CapEx spend starts to impact supply." But, he says, if demand continues to be stronger than usual, "the shortages could easily persist into the first half of 2023."

IDC's Rau also anticipates that companies need to prepare for at least another 12 months of problems: "Depending on semiconductor type and the system consuming the semiconductor, shortages of semiconductors will continue well into 2022," he says.

Covid-19 could still cause disruption for chip supply

While high demand has been at the heart of the global chip shortage, external factors have also played a role. “Other events have held back supply, such as fires in factories, power outages and the transportation blockage at the Suez Canal,” Rau says.

Covid-19 may have a continued impact too, with the highly transmissible Delta variant of the virus, which was first seen in India, now spreading to Taiwan, where many of the world’s semiconductors are produced. On Sunday Reuters reported some workers at chip packaging specialist King Yuan Electronics were being quarantined to contain a Covid-19 outbreak. Two other Taiwanese companies – packaging Greatek Electronics and ethernet switch-maker Accton Technology – have also reported cases.

All three companies are based in the Northern city of Miaoli, well away from Hsinchu, the country’s main chip production hub, where TSMC is based. Case numbers there remain low, but any surge in infections could cause further problems to already-stretched supply chains.