Hermann Hauser is unequivocal when asked to describe the health of the semiconductor sector in Europe. “It’s bad,” the Arm co-founder tells Tech Monitor. “We gave up [on semiconductors] at a time when we had some of the world’s leading companies, and other nations and regions produced a lot of support to build up their own semiconductor industries. Now we find ourselves in this ridiculous and very dangerous situation where there are only two companies in the world (Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung) capable of producing five-nanometre chips.”

Once a powerhouse of the chip sector, Europe is now a minor player in an industry dominated by companies from the Far East and the US. But with the issue of tech sovereignty high on the political agenda, due in part to the ongoing tensions between the US and China, and the ongoing global chip shortage which has highlighted structural defects in the semiconductor supply chain, Europe is planning to strike back.

Earlier this month, 22 member states agreed to work together on bolstering European chip production. “Europe has all it takes to diversify and reduce critical dependencies, while remaining open,” said Thierry Breton, European commissioner for the internal market. “We will therefore need to set ambitious plans, from design of chips to advanced manufacturing progressing towards 2nm nodes, with the aim of differentiating and leading on our most important value chains.”

But with nations including the US and South Korea planning big semiconductor investments of their own, Europe will need to make its own interventions in the market count if it is to regain some of the ground it lost.

How Europe lost its edge in chips

In 1990 Europe enjoyed a 44% share of the global chip manufacturing market, according to data from Boston Consulting Group. This was expected to fall to 9% last year and is likely to drop another percentage point over the next decade.

Europe’s ’90s chip prowess was largely built on success in the early mobile phone market of companies such as Ericsson, Nokia and Siemens, which built chips for their popular handsets. Elsewhere Europe “arguably had the best CMOS processor (a chip which stores core system information on computers) with [British company] Plessey”, Hauser says. The continent also led the way in the development of FGPAs, a type of integrated circuit widely used across different industries and in high-performance computers and data centres.

But lower labour costs in emerging markets soon became more attractive to manufacturers, while the emergence of the iPhone and other smartphones left European businesses behind. “A lot of companies withdrew from Europe for various reasons and it lost its competitiveness in the big semiconductor markets like memory and advanced logic,” says Risto Puhakka, president of semiconductor market analysis business VLSIresearch. “A degree of consolidation in the market was natural, and this loss of competitiveness wasn’t unique to Europe.”

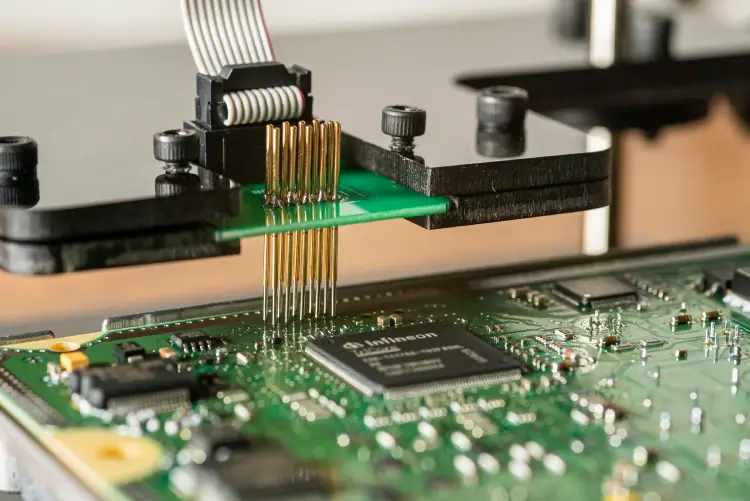

Puhakka says this has led to the development of several strong niches on the continent. “Where European semiconductor manufacturing has been strong is in automotive, power electronics and MEMS (microelectromechanical systems),” he says. “You could say Europe was forced to retreat to the niches that others weren’t super-interested in at the time, but building up those competencies over time has given them a nice position in those marketplaces.” Nevertheless, the revenue of Europe’s leading semiconductor makers – Infineon, STMicroelectronics and NXP – is dwarfed by that of the big players from elsewhere.

It is telling that neither of Europe’s most influential semiconductor businesses actually makes chips themselves. Dutch company ASML is one of the only suppliers globally of photolithography equipment used in the production of integrated circuits, while Arm has grown its business by supplying chip designs that can be manufactured by third parties. Set up by Hauser and his co-founders in 1990, Arm-based processors power the vast majority of connected devices and are increasingly being used in servers and PCs.

European Union semiconductor investment: how will it work?

In March, the EU set out an ambitious plan to grow its share of the global semiconductor market to 20% by 2030. To help with this, the European Commission has committed $160bn of its Covid-19 recovery fund to tech projects, with the continent’s chip capabilities likely to be prioritised for funding alongside improving 5G access and gigabit broadband capability.

Hauser, who now invests in deep tech companies through his VC fund Amadeus Capital Partners, is vice-chair of the European Innovation Council, an EU organisation that supports businesses developing new technologies, and says the Commission’s intervention is being driven by a desire for greater tech sovereignty. “Semiconductors are a critical technology you have to have to run your government and your economy,” he says. “So if you don’t do something yourself you create these one-sided dependencies, usually on the US or China, which allows them to coerce you into doing things you don’t want to do.”

He believes convincing TSMC or Samsung to build a manufacturing base in Europe is vital. “The game is in scale manufacturing, and what America is doing – correctly – is inducing TSMC to build a factory in Arizona. Samsung is investing $20bn in the US, and clearly, we have to do the same in Europe because they’re the only people who know how to do this stuff.”

Breton has held talks with TSMC and US chip manufacturer Intel, but the early signs are not positive. Mark Liu, TSMC’s chairman, called Europe’s plan “unrealistic” during a speech to the Taiwan Semiconductor Industry Association, adding it would lead to a large amount of “unprofitable capacity”. TSMC is more likely to double down on planned investments in the US, Reuters reported last week.

Meanwhile, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said on a recent trip to Europe that it would take a package of subsidies totalling more than $8bn to convince his company to open a new chip foundry on the continent.

Puhakka says a better bet would be for Europe to focus on growing its own companies, pointing out that chips for power electronics, where European companies excel, account for about a quarter of the global semiconductor market. “TSMC is not necessary for Europe to be successful in semiconductors,” he says. “What’s needed is sustained continued investment into European companies, and if the governments decide to participate in that, great. If you want to have factories in Europe for geopolitical reasons to shore up your supply chains, you should do that with Infineon, STMicro and NXP first and make sure those supply chains stay on European soil.”

One advantage Europe has if it attempts to bring the likes of TSMC or Samsung to the bloc is that it is easier to subsidise companies for commercial purposes than in the US, where they tend to be tied to defence projects, Puhakka explains. “Europe has supported [aerospace giant] Airbus with long-term consistent investment which isn’t coupled to defence needs,” he says. “In the US, defence always plays a huge role in things like this, whereas the European Commission can engage with companies without defence interference to find better solutions. That might be a nice advantage.”

Post-Brexit Britain’s role in Europe’s chip ambitions

Though Europe is thinking big when it comes to growing its semiconductor industry, Gartner vice president analyst Alan Priestley says it needs to be realistic about how much sovereignty it will be able to gain in this area. “Europe has this desire for more fab capacity, but the issue is that fabs will make a certain set of products, not every product,” he says. “Even if you build another fab in Europe, its output won’t remain in Europe. It will go to Asia for assembly and test, and to China to integrate into products, and then some of those products will be shipped back to Europe.” He adds: “I’m not sure if it’s even possible for Europe to be self-sufficient on this because the global supply chains are pretty complex.”

This reliance on other countries could be even more acutely felt in post-Brexit Britain as it renegotiates its relationships with the major world powers. Although it has left the EU, Hauser says Britain will need to closely align itself with its neighbours if it is to keep control of its own tech sovereignty. “Clearly there are only three regions in the world that have a cat in hell’s chance of being technologically sovereign – the US, China and Europe,” he says. “Brexit or no Brexit, Britain has to side with Europe on this because that’s the only way it can retain its technology sovereignty. On its own, there’s no way it can be sovereign in areas like semiconductors and 5G.”

One positive step, he believes, would be for the UK government to intervene in the proposed sale of Arm to NVIDIA by its current owner, SoftBank. The $40bn deal is currently being scrutinised by regulators around the world, including the UK’s competitions and markets authority. Hauser rates the chances of the sale going through as less than 50%, and believes the business could instead be relisted on the London Stock Exchange, with the government spending $1bn on a “golden share” to protect the company as a British asset.

“If you look at the deal, NVIDIA is proposing to pay $12bn in cash,” he says. “If the government put up $1bn and took a ‘golden share’ the market would easily find the other $11bn. I’ve been talking to a lot of people in the City about this and I think relisting on the London Stock Exchange would be a very positive outcome.”