With the global chip shortage showing no signs of abating, South Korea has become the latest country to announce significant investment in semiconductor development as its companies bid to meet surging demand and keep pace with rivals in Taiwan and the US. The $451bn package, combined with other planned investments around the world, could eventually lead to a surplus of manufacturing capacity, experts believe.

The funding, which will come over the next decade, will predominantly be provided by South Korea’s two leading semiconductor companies, Samsung and SK Hynix. Samsung is investing $151bn in its non-memory chip foundries over the next ten years, an increase of $33.6bn on previously announced plans. Meanwhile, SK Hynix, which earlier this year pledged to build four new chip foundries at a cost of $106bn, will also invest an additional $97bn upgrading its existing manufacturing facilities.

Meanwhile, the South Korean government says it will offer tax breaks and incentives for chip businesses, fund the training of 36,000 new staff, and spend $1.3bn on semiconductor R&D. Local authorities around the newly created K-semiconductor belt, an area south of Seoul where much of the investment is focused, will be encouraged to invest in their water and power networks to ensure facilities have an adequate supply.

The global chip shortage is a big problem that needs big investment

South Korea is acting in response to chip industry investment plans from other parts of the world. Taiwan’s TSMC, the manufacturing market leader, says it will pump in an additional $100bn to its manufacturing capacity over the next three years, while Intel is spending $20bn to build two foundries as part of its new manufacturing strategy.

South Korea is the overall market leader, but more importantly is one of three countries, along with the US and Taiwan, that is responsible for producing the vast majority of leading-edge chips found in smartphones and computers. Even taking into account the low-end chips used for more basic applications, which tend to be produced in China or Japan, the three countries occupied 61% of the manufacturing market in 2019.

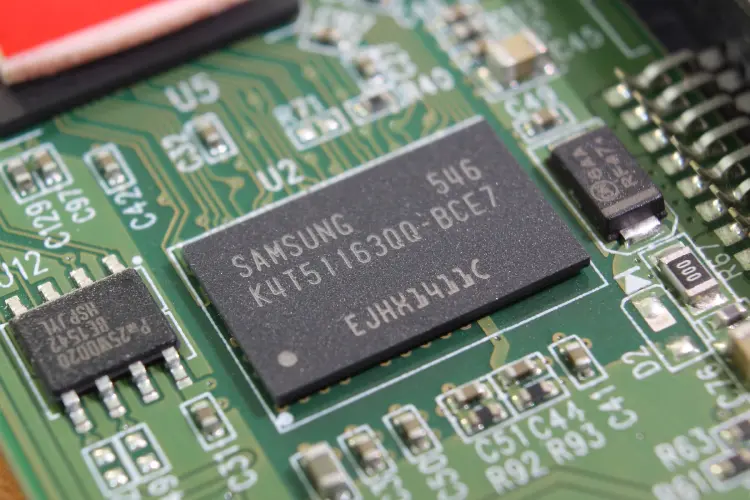

South Korea is particularly dominant in the memory chip market, with Samsung and SK Hynix holding 71% of the global DRAM market in the first quarter of this year, according to figures from research company TrendForce.

Maintaining this market share is an expensive business, and it is no surprise that South Korea is prepared to invest significant sums, says Jim Feldhan, president of Semico Research, which covers the chip industry. He says the investments represent a “substantial amount of money”, and indicate that “governments such as South Korea are recognising the strategic importance of chip manufacturing as semiconductors permeate the global economy”.

But the figures are not exceptional considering the ten-year time frame, Feldhan adds. “To put this in perspective, the top three semiconductor companies – Intel, Samsung and TSMC – have been investing an average of $10–$15bn a year over the past several years,” he says. “In fact, Samsung’s total capital expenditures were over $25bn in 2020.”

Alan Priestley, vice-president analyst at Gartner, agrees. “There’s an incentive at the moment to put in place more capacity because the shortages have brought the semiconductor industry to the attention of politicians,” he says. “This stuff costs money and takes time – if you try and put a million in, you’re just buying the coffee for the first round of meetings. [The South Korea investment] is the sort of funding you need to put on the table if you’re going to invest in leading-edge production.”

After the chip shortage, is a surplus on its way?

The current shortage has mainly concerned the production of older generations of chips such as those used by the automotive industry. These are traditionally produced on 200mm silicon wafers, but a lack of investment in this sort of technology, with manufacturers focusing on newer 300mm wafers instead, has led to supply drying up.

Priestley says Samsung and its rivals will be investing in their 300mm capabilities, but that production of older chips can be shifted across to these larger wafers. “The problem with [200mm] is the equipment,” he says. “You can’t get the manufacturing equipment, the tools and furnaces. It’s probably better to move your 200mm production over to 300mm.”

When all these new foundries come online, might the current shortages be replaced by a surplus of capacity? “Semico does have some concern that there will be an overabundance of capacity in certain markets,” says Feldhan. “But this will turn into lower prices for the consumer and, most likely, new applications with innovative products.”

Priestley says the industry is likely to have more capacity than it needs as new factories are built, but that this will be a temporary phenomenon. “Once the companies build out their new foundries we’ll go into a period of oversupply, because you can’t put this kind of capacity on in small increments,” he says. “When you’ve got a factory in place it might be capable of running 100,000 wafers a month, and it’s not like a car manufacturer where you can slow production, or down tools and come back a week later. It’s a continuous process.”

But, Priestley assures, the growing demand for semiconductors means the industry is likely to remain in a pattern of manufacturing shortages and surpluses. “The capacity they’re putting in place now will be enough for the next few years, and as these things come on stream there’ll be too much capacity,” he explains. “But then, in another five years, we’ll be maxing out capacity again because everyone wants the latest smartphones, and we expect to see demand for things like smart homes and electric vehicles increasing.

“The industry is very cyclical; that’s just the nature of the beast.”