The majority of car industry insiders expect the automotive chip shortage to stretch into 2022, according to new research. This growing pessimism around the scale of the crisis could cause a rethink of how tech supply chains in the sector operate as manufacturers reconsider the strategic importance of semiconductors.

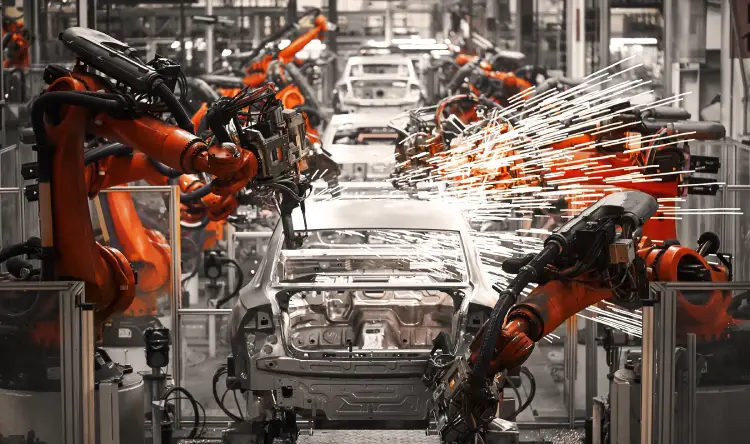

A global shortage of semiconductors, caused in part by the Covid-19 pandemic and the increased demand for electronics, has affected a wide variety of business sectors this year. Automotive has been hit particularly hard, and this week Volkswagen warned managers to prepare for bigger delays to production in the upcoming quarter than it has seen so far in 2021, the Financial Times reported. In the UK, Jaguar Land Rover announced on Friday that two of its plants would close temporarily due to the shortage.

With factories around the world having been shuttered for weeks at a time as a result of the crisis, new analysis from data analysts GlobalData shows that the opportunity cost to manufacturers of not building new cars currently stands at $47bn.

The automotive chip shortage: the worst is yet to come?

GlobalData has surveyed more than 100 car industry professionals in recent months to gauge their views on the automotive chip shortage, and the results show growing scepticism that the problem will be resolved quickly. Only 17% of those polled on March 25-28 felt the crisis would stretch into 2022, but when the same group was questioned in the week of April 19-25 that number had grown to 58%.

The shortage is partly being exacerbated by panic buying from OEMs that supply the industry, meaning the problems are likely to be more drawn out, says Calum MacRae, head of automotive at GlobalData. “Tactically, some of the OEMs have ordered more than they need, which causes problems elsewhere,” he explains. Demand is also being driven up by Joe Biden’s Covid-19 stimulus package in the US, says MacRae, with citizens receiving up to $2,000 from the government. “A lot of people have that money burning a hole in their back pocket, and are putting it down on a car,” he says.

TSMC, the world’s largest producer of semiconductors, has said it is now trying to prioritise production of automotive chips where possible. This move comes after the Taiwanese firm was approached by the US government, as well as ministers from Germany and Japan, to try and find solutions to the crisis. In the longer term, planned investments by TSMC and leading manufacturer Intel in production capacity could help avoid future issues.

Automotive analyst Asif Anwar, a director at Strategy Analytics, takes a more optimistic view of when the shortage will end, suggesting suppliers could see an easing of problems in the last two quarters of 2021. But, he says, its impact has been significant. “We believe that there remains a scenario where the ongoing challenges in the supply chain will result in vehicle production being impacted further than originally estimated,” he says. “The loss in production attributable to semiconductor constraints could be as high as 5–10% for 2021.”

Will we run out of new cars?

With 92.8m new motor vehicles produced globally in 2019, a 10% drop could have serious supply consequences. MacRae believes that the US market will be worst hit.

“The problem is going to be worse for consumers in North America than in Europe or the rest of the world, because in the US people want to buy a car off the lot, there and then, whereas in Europe we’re used to waiting a few months,” MacRae says. “In the US the companies usually carry anything between 60-90 days worth of inventory, but we’re seeing reports that that is already down to 30-40 days. That could really stymie the industry’s recovery phase [from Covid-19] because people won’t be able to get the vehicles they want.”

Anwar says manufacturers are prioritising models which are “most popular or most profitable”, and adds “in that respect, it’s unlikely anyone will notice a shortage of vehicles. At the production sites maybe inventory is starting to look a little bit tighter, but so far they have been able to mitigate the situation by really focusing on what consumers want.”

Will the automotive chip shortage cause a supply chain rethink?

Elon Musk, founder of Tesla, the world’s most valuable automotive company, told a call with investors on Monday that his business had been able to avoid the worst of the shortages by adapting quickly so its vehicles could run different chips, while also developing software which enabled it to source semiconductors from new manufacturers. “We’re mostly out of that particular problem,” Musk said.

Other producers have not been able to be as agile, and MacRae says the problems could cause a rethink on their relationship with technology. “The OEMs need to consider how strategic chips are for them, rather than viewing them as a commodity that they try and get for the cheapest price,” he says. “That means reconsidering supply chains.”

One of the few traditional manufacturers to have ridden out the storm relatively well is Toyota, MacRae says. “They are the only automotive company that really understands chips because they did a complete re-evaluation of their supply chains after the Fukushima disaster,” he says.

Toyota is known as the pioneer of just-in-time lean manufacturing, where it holds as little inventory as possible, but MacRae explains it makes an exception for chips. “If it’s a strategic supply [like semiconductors] they’re happy to keep stock in the warehouse or have it in the pipeline,” he says. “That’s why they’ve come through this crisis fairly well and haven’t been hit as hard as others.”