The takeover of the Newport Wafer Fab (NWF) semiconductor manufacturing plant by Nexperia was confirmed on Monday afternoon, ending weeks of speculation about the deal. Industry analysts say the deal makes commercial sense and may provide stability for NWF, which has a chequered ownership history. But the fact that Chinese-owned Nexperia is now in control of the UK’s largest chip factory has caused consternation amongst MPs at a time when countries around the world are trying to take greater control of their domestic chip-making capabilities.

Nexperia, which is based in Holland but owned by a Chinese company, Wingtech, is already the second-largest shareholder in NWF and a major customer of the foundry. Under the new deal, it will take full control of the plant, which employs 400 people in Newport, South Wales and will be renamed Nexperia Newport. Nexperia already has two other chip factories in Europe, Manchester in the UK and Hamburg, Germany.

“Nexperia has ambitious growth plans and adding Newport supports the growing global demand for semiconductors,” said Achim Kempe, the company’s chief operations officer. “The Newport facility has a very skilled operational team and has a crucial role to play to ensure continuity of operations. We look forward to building a future together.”

Paul James, managing director of NWF, hailed the deal as “great news for the staff here in Newport and the wider business community in the region”, with Nexperia set to provide “much-needed investment and stability for the future”. Industry experts told Tech Monitor that the move could end years of uncertainty about the plant’s ownership.

What is the Newport Wafer Fab?

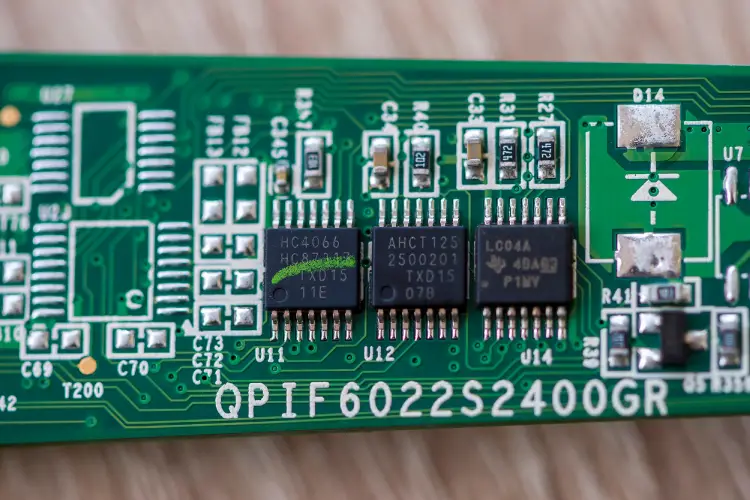

Founded in 1982 by British semiconductor company Inmos, NWF now primarily manufactures power electronics chips used chiefly in the automotive industry. It has had a chequered ownership history in recent years, and Nexperia is taking control by buying out majority shareholder Drew Nelson, who bought a controlling stake in the business from German chip maker Infineon four years ago.

Despite being the biggest facility of its kind in the UK, the plant’s global significance is limited. “Newport Wafer Fab is quite small in the scheme of things, even in power semiconductors,” says John West, managing director at VLSI Research. But, he says: “Both companies do have some useful manufacturing and device testing know-how that would be difficult to shift to Asia in the short to medium-term.”

West points out that even though Nexperia has been owned by Wingtech since 2019, most of its product development and testing work is still carried out in Europe, with the company investing to grow its Manchester plant. “The deal is not bad for NWF as it has had multiple owners over recent years and having an owner that ‘knows’ its business may be a good thing,” he argues.

Newport Wafer Fab takeover: the geopolitical implications

Terms of the deal have not been disclosed, though it is reported to be costing Nexperia £63m. NWF has debts of £38m to HSBC and the Welsh government which will be paid off by its new owners, according to a source quoted by CNBC.

Though this pushes the value of the deal to around £100m, the price is still low for a chip fab. Mike Orme, who covers the semiconductor market for intelligence provider GlobalData, says the purchase “is part of a long-term piecemeal approach by China to dot the world with Chinese-controlled fabs of all shapes and sizes”.

Orme says the site could have great strategic value for China. “The plant currently supplies 28nm or above power management chips, but may well be used to experiment with chips made from compound materials – a major Chinese priority,” he says. Compound semiconductors are those made from silicon and at least one other material, such as gallium nitride, which can offer performance advantages.

A Chinese-owned company taking control of a British chip-making asset has raised eyebrows at Whitehall. The global chip shortage has put a spotlight on the vulnerability of semiconductor supply chains, with the vast majority of production being carried out by two companies, Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung. As a result, countries such as the US and Japan have been investing in domestic chip capacity to try and reduce their reliance on foreign suppliers, while Europe has plans to build out its own capabilities.

Conversely, the takeover of NWF means UK-controlled semiconductor manufacturing capabilities are diminished, but according to a letter to MPs leaked to the Telegraph, business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng said the government had looked at the deal but had decided there were no grounds for it to intervene. This contrasts with the government’s position on chip designer Arm’s proposed takeover by US rival NVIDIA, which is currently subject to a probe by the Competitions and Markets Authority.

On Wednesday, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the government would be investigating the deal after all. Speaking to MPs on the parliamentary liaison committee, he said Sir Stephen Lovegrove, the national security adviser, would be looking into the take-over. “We have to judge whether the stuff that they are making is of real intellectual property value and interest to China, whether there are real security implications,” Johnson said.

Conservative MP Tom Tugendhat, who chairs parliament’s foreign affairs committee and is part of the China Research Group of MPs, says he was surprised the deal had not already been investigated under the National Security and Investment Act, which was introduced earlier this year and gives the government power to scrutinise deals such as the NWF takeover on national security grounds.

“The semiconductor industry sector falls under the scope of the legislation, the very purpose of which is to protect the nation’s technology companies from foreign takeovers when there is a material risk to economic and national security,” said Tugendhat in an emailed statement on Tuesday, before Johnson’s announcement. “This is the first real test of the new legislation. The government is yet to explain why we are turning a blind eye to Britain’s largest semiconductor foundry falling into the hands of an entity from a country that has a track record of using technology to create geopolitical leverage.”

Tugendhat says many of the UK’s allies “have expressed serious concerns about this deal”, and Orme says pressure from elsewhere could also cause a change of heart, particularly if the government faces sustained opposition from the other members of the ‘Five Eyes’ security alliance – the US Canada, Australia and New Zealand: “The government seems awfully lax about the whole thing, but may be shaken up by its Five Eyes partners to think again,” he says.