Facebook and Amazon are seeking US government approval to operate a new undersea internet cable between the Philippines and California. Originally a project with China Mobile, the Chinese telecoms company agreed to step down following US government concerns over Chinese companies handling network traffic. The development is emblematic of the newly fraught geopolitics of internet infrastructure, where the US is determined to prevent China from building and operating submarine cables that could touch sensitive US data.

The CAP-1 cable, expected to launch in 2021 and span 12,000km, will connect California to the Philippines. A Facebook spokesperson told Reuters that the project parties agreed “the best path forward to complete the construction and bring the… cable system into operation was to restructure the system ownership…”

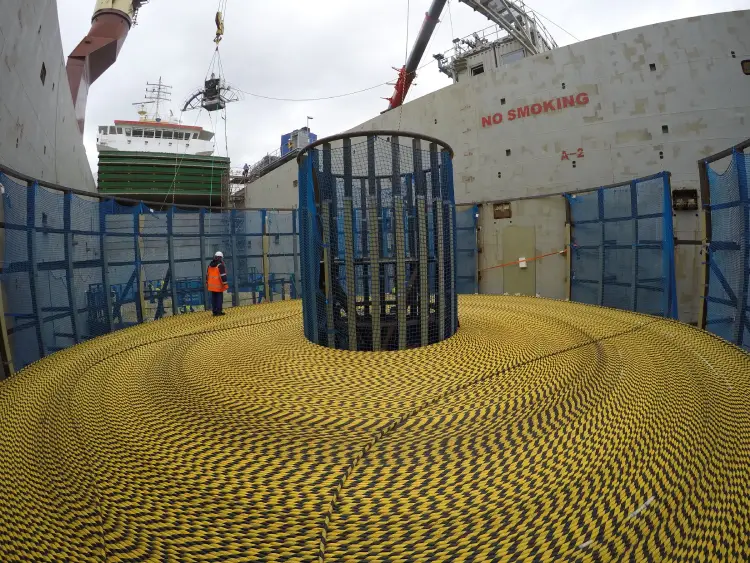

The world’s 426 subsea internet cables ferry practically all internet and voice connectivity internationally. The vast majority of this infrastructure is owned or operated by American companies, and the US is keen to keep it that way, voicing ever-louder opposition to China’s involvement in building such cables.

Last year, then-US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo claimed the international community must “ensure the undersea cables connecting our country to the global internet are not subverted for intelligence gathering by the People’s Republic of China at hyper-scale.”

American companies Google, Facebook and Amazon have become leading investors in internet infrastructure in recent years, but US fears over China have translated into interventionism that has complicated planning for these projects.

The geopolitics of submarine cables and US interventions

The US first vetoed a subsea cable project for security reasons in 2019. The Facebook and Google-funded Pacific Light Cable Network was meant to connect Hong Kong and other Asian countries with the US. But after the US claimed the Hong Kong leg could expose data to China, the cable’s path had to be altered. The FCC application for CAP-1 – originally known as the Bay to Bay Express Cable System – was withdrawn shortly after the Pacific Light Cable Network’s application was denied.

“CAP-1’s transition from the Bay to Bay Express Cable System and subsequent exit of China Mobile from the project is a test of how ‘American’ submarine cables connecting the US and Asia must be to meet evolving US standards of communications security,” says Lane Burdette, researcher at Texas A&M University. “This move follows a trend of increasingly formalised regulation by the US government of submarine cable construction and operation. Not only is cable routing seen as key to determining information security, but cable ownership as well, especially in the case of China.”

Not only is cable routing seen as key to determining information security, but cable ownership as well, especially in the case of China.

Lane Burdette, Texas A&M University

Tech Monitor has previously covered how US-China tensions are playing out in the Pacific. When the tiny Pacific island nation of Palau solicited offers for a new subsea cable in 2020, Washington intervened to warn it off opting for cheap Chinese infrastructure. The cable ended up being funded by a loan – the very first of its kind – issued by a trilateral partnership of Australia, Japan and the US. The episode demonstrates the degree to which the US and its allies are keen to fend off low-ball bids from Chinese telecoms companies, which on a pure cost basis are often the most attractive for infrastructure projects.

“Recently, all three bids in a tender process for the East Micronesia cable [designed to improve connectivity for the island nations of Nauru, Kiribati and Federated States of Micronesia] were rejected and it’s possible that decision may have been because of, or influenced by, concerns about Chinese involvement in at least one of the bids,” says Dr Amanda Watson, a researcher with Australian National University. Reuters reports that, according to sources, the World Bank-led project declined to award a contract after Pacific island governments heeded warnings from Washington that Chinese companies could pose a security threat.

Are US fears over submarine cables justified?

US fears over Chinese companies’ involvement ostensibly centre on the use of cable-tapping to conduct surveillance. This is a pattern of activity the US itself engages in, as demonstrated by the Snowden leaks. But there is some scepticism over how great this threat is, given that cables already directly connect the US and China, and that blocking particular cable landing points will simply mean traffic is routed through a third country. “A key trait of submarine cables is not only their connectivity but their interconnectivity, such that data moving along one cable may transfer to another in order to reach an end destination,” says Burdette.

But regardless of whether US concerns are founded or not, they will continue to have material consequences on the future construction of subsea cables, and possibly constrain which cables American companies can route traffic through.

Earlier this year, Facebook was obliged to withdraw from the Hong Kong-Americas cable project, another cable intended to link the US with Hong Kong and Taiwan. In the face of US pressure, “there may be a shift from routing through Hong Kong in favour of other major hubs like Singapore and Taiwan,” says Burdette. Facebook has planned two more subsea cables, Echo and Bifrost, which will connect the US with Indonesia through Singapore, managing to “mitigate geopolitical tensions by avoiding the South China Sea altogether”.

A bifurcation of the internet between the US and China would have serious ramifications. “The associated challenges will be to investors in Chinese tech companies, and the related supply chain issues that result from this decoupling,” says Robert Spalding, senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, a think tank that promotes American leadership. “US tech companies have realised the importance to their business of undersea cables, but now they can expect scrutiny from the US government with regard to how and where they deploy.”