The record was broken on 31 May. Until that date, Palau – an archipelago of some 340 islands just over a thousand miles east of the Philippines – had reported no cases of Covid-19. As a result, ordinary citizens were free to conduct their daily business in much the same way as they’d always done, unrestrained by the kinds of lockdowns that blanketed much of the rest of the world.

The question for many Palauans, however, was what actually could be done. Keeping Covid-19 out of the islands meant keeping out the tourists, the lifeblood of the country’s economy. Across Palau, hotels stood dormant and beaches lay empty. All the while, a single subsea internet cable, thickly insulated with plastic surrounding glass fibres pulsing with light, kept the nation connected with the outside world.

“We actually have very high internet use around the islands,” explains Ongerung Kambes Kesolei, editor of the Tia Belau, one of Palau’s two newspapers. 4G is within easy reach of most citizens on the islands, along with plentiful broadband services. “Pretty much everybody is on YouTube or Facebook.”

In October, Palau announced it was in the market for a second subsea cable. A 2019 incident in which Tonga was cut off from the world after its sole undersea cable was accidentally severed helped convince the government that it was time to invest in a back-up option. What made the decision unusual, however, was how the project would be initially funded: not by a consortium of experienced cable-laying companies, but from a loan – the very first – issued by a trilateral partnership of Australia, Japan and the United States.

The announcement was a signal that the US and its allies are serious about providing an alternative for Pacific nations to the many lowball bids from Chinese companies for similar projects across the region, from the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea to Kiribati, Micronesia and Nauru. Such attempts have been greeted with alarm by Washington, livid at the prospect of Beijing not only dangling the lure of increased investment in infrastructure to entice Pacific nations into its orbit, but potentially tapping into the subsea cable landing points to conduct mass surveillance. As a result, numerous cable projects across the region – including those operated by Google and Facebook – have been diverted, cancelled or taken over by Western consortiums in an ad hoc fashion.

But are the security concerns cited by these great powers justified? And are the Pacific nations well-served by this deepening rivalry between Washington and Beijing?

Subsea cables: the backbone of the internet

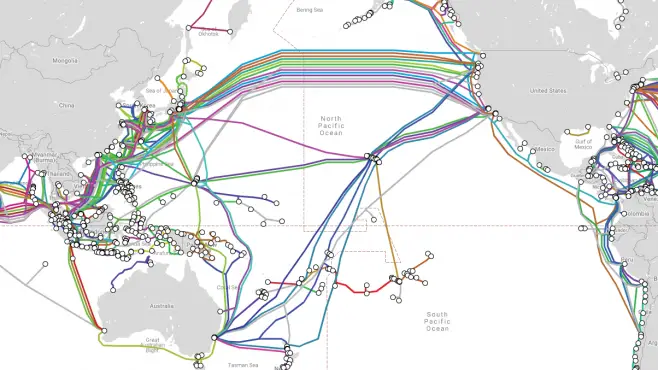

The internet as we know it would not have existed were it not for subsea cables, says Nicole Starosielski, NYU professor and author of The Subsea Network. “Fibre-optic cables were already part of the picture” during the days of dial-up, she says. Before today’s satellite communications network was set in orbit, they were the only way to carry a connection over the ocean. Even now, satellite-borne internet traffic is dwarfed by subsea cables, which carry an estimated 95% of all traffic between continents and islands.

While plenty of cable was laid across the Atlantic in those early days, the Pacific had to wait its turn. A combination of low demand and high costs meant that anyone who wanted to surf the web had to resort to a satellite connection. Coverage, recalls Kesolei, “was usually weather dependent,” with tropical storms often causing sustained outages. This began to change, however, in the early 2000s, when prepaid mobile operators entered the Pacific market. “That really drove a massive expansion of the telecommunications industry right across the region,” says Shane McLeod, a research fellow at the Lowy Institute. “Then, alongside that, came the demand for bandwidth.”

Progress was slow. The Marshall Islands would only receive its first subsea cable in 2010; Vanuatu in 2014; Palau in 2017. Gone were the rain-induced outages, but the threat of disconnection persisted. Subsea cables are vulnerable to everything from ship’s anchors to tsunamis and earthquakes, mudslides – even sharks. If an island nation only has one cable, disconnection can plunge it into economic chaos, as the Marshall Islands and Tonga both discovered in recent years.

As such, demand for back-up cables is growing – and the People’s Republic of China is only too willing to step in. The country has already invested some $6bn so far in infrastructure across the Pacific region, as part of its Belt and Road investment initiative. Chinese companies led by Huawei Marine have also been at the forefront of bids for new subsea cables in Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Kiribati. The latter two projects, however, were deemed unacceptable security risks by the Australian and US governments. Australia outbid a Chinese consortium in 2018 and the US issued a formal security warning to three Pacific nations not to entertain bids from Huawei Marine.

The perceived threat draws from one central assumption: that Chinese funding of subsea cables will entail some measure of control that would permit Beijing to intercept traffic flowing along the cables and thereby conduct mass surveillance on Western nations. Reported connections between Huawei Marine and associated companies to the Chinese government, combined with the fact that Western governments are known to tap into subsea cables themselves, have been taken as reasons enough for the diversion and reconstitution of several such projects.

Starosielski believes these security concerns are vastly overstated. Diverting cable projects “is like putting up concrete walls but not locking the windows if someone’s trying to break into your house,” she says, given the innumerable hacking methods at the disposal of the Chinese intelligence services and the fact that it is impossible to predict how data packets actually flow through international cable networks. If, for example, Facebook’s cable between the US and Hong Kong had been permitted to operate, there would be a chance that a conversation between a user in Singapore and Oregon could be intercepted by Chinese intelligence. Indeed, “it might have transited through any other number of points” along intra-Asian networks, explains Starosielski. “It doesn’t mean it’s not transiting through Hong Kong, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it is.”

(Photo by Patrick Hamilton – Pool/Getty Images)

The soft power of subsea internet cables

Why then, would the US and its allies show any interest in funding new cable systems in the Pacific? Starosielski believes that the answer has everything to do with their exertion of soft power in a region long starved of investment. For both the US and Pacific nations, cable projects are more than just a bundle of glass fibres and plastic insulation but visible symbols that “celebrate an ideal of connection” with the rest of the world, says Starosielski. As such, they can easily become objects of anxiety, visible tokens of the ebb and flow of soft power in the Pacific.

These are combined with fears that subsea cables are just one of the ways in which China is dragging Pacific nations into its orbit by ensnaring them in debt. Demand for reliable communications infrastructure in the heavily forested and economically underdeveloped Papua New Guinea, for example, is strong. In 2019, it welcomed the laying of the Kumul submarine cable network by Huawei Marine. Concerns have emerged, however, about how PNG will pay off the $298m it borrowed from China’s Exim Bank to fund the project, in addition to other debts it owes for a new international airport, a court complex, road projects and a (non-operational) data centre.

Analysing the construction of subsea cables through the lens of competition between the US and China alone, however, obscures the agency wielded by Pacific island nations throughout this process. Indeed, argues Dr Amanda Watson of the Australian National University, the choice of whether a Chinese or Western consortium wins a bid to lay cable has more to do with regional politicians trying to find the best deal on infrastructure that they can get, given that their countries are already wreathed in debt. “Some of them would be savvy enough to realise that there is some geopolitics and strategic competition issues going on,” she says. “But I think if a Pacific Island leader is trying to get services for their people, then they’re perhaps just trying to get services for their people.”

In that sense, Chinese investment in subsea cables must also be seen within the context of a historic lack of Western interest in the Pacific region. The deepening rivalry between Washington and Beijing could help to reverse that situation, not least in its potential to drive down the price of bids.

“I think that’s been one of the big changes in the region over the last few years,” says McLeod. While the trilateral partnership’s funding model may serve as a signal to China that the US and its allies are keen to check the progress of Belt and Road diplomacy, it is also another manifestation of a more altruistic stance toward infrastructure funding that has taken root over the previous decade. “Five, ten years ago, Australia wouldn’t want to build infrastructure. They’d be very much about supporting the operations of government through supporting people, as opposed to building things.”

For Palau’s part, PC2 will provide the kind of back-up that will allow it to avoid the outages that have assailed its neighbours. The cable’s construction has also been folded into a much broader conversation about the country’s place in the world. Palau is one of only 15 nations to recognise Taiwan, automatically excluding it from relations with mainland China. In return, Taiwan has been generous in its provision of tourists and development aid to its island neighbour. Even so, Palauans are open to exploring their options.

There are elements in Palau who think that Palau is better off having China on its side.

Kambes Kesolei, Tia Belau

“There are elements in Palau who think that Palau is better off having China on its side,” says Kesolei. “They say that Palau cannot continue to ignore China’s military and economic might, as well as China holding a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.”

For now, though, there are no signs that Palau intends to embrace Beijing over Washington. Likewise, the PC2 project is a signal, says Kesolei, that Washington “regard[s] this region as important.” Ultimately, says McLeod, all this politicking over cables could be good for the region.

“It can give Pacific nations options,” says McLeod. “The sovereignty of countries in the region is their number one asset, the one number one thing that they protect and guard. And that’s something that they can use to their advantage to get the development that they need.”