Regulatory and safety issues present major barriers to metaverse adoption, say the majority of UK IT professionals. The findings, gathered in a survey by BCS, the UK’s Chartered Institute for IT, were presented to a group of cross-party MPs during a panel session on the future of the metaverse and Web 3.0 on Tuesday.

Monday’s meeting of the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on the metaverse, the idea that business and social interactions could take place in virtual worlds, and web 3.0 looked at what the future held for the technology. It heard from academics and technologists, as well as representatives from OpenUK, Nominet, S&P Global Market Intelligence and former employees of Twitter and Facebook.

During the panel, delegates brought up several issues with the current landscape surrounding the metaverse and web 3.0, such as a lack of skills, gender bias, and the regulatory challenges within the UK.

The BCS research, released on Monday, that shows most technology professionals survyed are concerned about safety issues in the metaverse (77%) and the regulatory challenges the metaverse will create (81%). The study of 1,036 BCS members also showed that only a fifth of professionals had confidence that the UK’s digital skillset would be compatible with both the metaverse (19%). This rose to a quarter for Web 3.0 (26%).

Experts are still struggling to define and measure the metaverse

As part of the metaverse APPG session, experts were asked to provide a definition of the metaverse to cross-party MPs but struggled in pinning down the specifics. One expert commented that rather than defining what the metaverse is now, it was more important to define what it would be in the future.

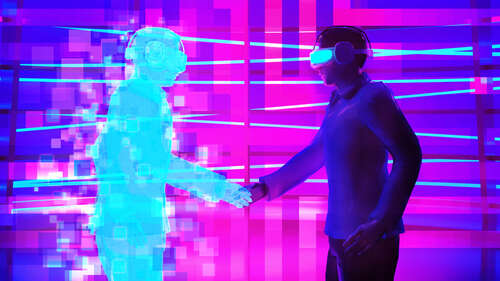

The BCS report describes the metaverse as a 3D digital space that uses virtual reality to allow people to have lifelike experiences online. However, it found that both the metaverse and Web 3.0 lacked clear, accepted definitions that could be easily translated for both professionals and the public.

BCS also emphasised that the metaverse was more than just about “disappearing” from the physical world, but about how people communicate online. It also told MPs that the use cases were more than just using the technology for pleasure but for education, training and healthcare.

The hearing was told that these are use cases where people are not necessarily going into the metaverse to have an experience that is measurable, but that it could still provide value and become a useful tool, particularly for vulnerable societies.

The virtual environment isn’t safe or secure

The BCS team commented that despite the potential benefits to society, metaverse applications are currently secure enough to be used in the realms of education or healthcare. They said the speed at which the technology is growing in popularity means appropriate guardrails are not yet in place.

BCS members agreed – in its study, 81% of respondents believed that the metaverse would create new regulatory challenges. Over two-thirds said they were concerned about safety issues.

“Tech professionals think the safety of potential metaverse users, especially children, is a big concern, as the boundaries between the real and the digital world become blurred,” Rashik Parmar, chief executive of BCS, said. “They tell us that regulation, safeguarding issues and depth of available skills all need to be resolved before the metaverse can become part of everyday life.”

The ‘big boys’ are making the metaverse decisions

The co-chair of the meeting, Baroness Manzila, told the room that fears of monopolies on the metaverse were justified. She described the companies that “held the decisions” on technology as the “big boys.”

“You talked about the monopoly or the fear of monopoly being held – I think it’s already there,” she said. “I think the large big boys are already holding the decisions about how to frame a part of the metaverse, not all of it perhaps.”

Companies such as Facebook parent company Meta have invested heavily in metaverse technologies, while other Big Tech businesses such as Nvidia have built platforms and applications for virtual worlds.

Parmar also believes that the metaverse needs to learn from the mistakes of social media: “Immersive technology, just like AI, should be built and maintained by teams of ethical, highly competent, inclusive professionals to give us a better chance of avoiding the mistakes still seen with social media,” he said. “Ideally, we should be able to hold individuals and organisations running the metaverse to some agreed standards of professional accountability.”

Open-source key to fostering UK innovation

On the topic of fostering innovation within the UK, one speaker, Amanda Brock, CEO of OpenUK, said more metaverse platforms need to be built on open-source technologies, and that the government must back up its “open-source first” policy to enable more innovation in this space.

“Where you see technology really adopted on a global scale, it tends to be that it’s created as open source,” she explained. “It crosses geopolitical boundaries because the collaborators who created [the technology] and the investment comes from all over the world.”

To take a step forward, Brock said that the UK government needed to adopt a second layer of processes: “The [open-source first] policy creates an environment where you would put an open source licence on government-funded innovation,” she said. “But that isn’t enough, you actually need the practises that sit with it and embedding those practices into the environment where governments are spending millions and billions of pounds.”

Read more: How tech leaders should approach the industrial metaverse