The team behind Project Silica – a Microsoft Research project that uses lasers and artificial intelligence to store data in quartz glass – have successfully managed to store and then retrieve the 1978 Superman film on a small piece of glass.

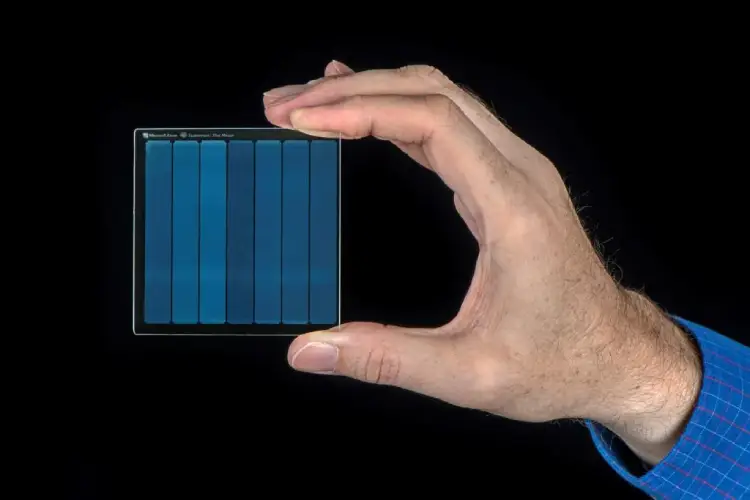

The project – based largely in the UK via a collaboration between Microsoft’s Cambridge-based research centre and the University of Southhampton’s Optoelectronics Research Centre – uses lasers that emit pulses faster than one trillionth of a second to encode data in glass; in this case on a piece 75mm by 75mm by 2mm thick.

“Storing the whole ‘Superman’ movie in glass and being able to read it out successfully is a major milestone,” said Mark Russinovich, Azure’s CTO: “I’m not saying all of the questions have been fully answered, but it looks like we’re now in a phase where we’re working on refinement and experimentation, rather asking the question ‘can we do it?’”

A laser encodes data in glass by creating layers of three-dimensional nanoscale gratings and deformations at various depths and angles, Microsoft’s Jennifer Langston explained in a blog today. “Machine learning algorithms read the data back by decoding images and patterns that are created as polarized light shines through the glass.”

Microsoft/Project Silica teamed up with Warner Bros. to deliver this particular milestone. The company has a library of films and has been looking for a storage technology that could, in theory, last centuries, withstand floods or solar flares and that doesn’t require being kept at a certain temperature or need constant refreshing. (The company currently refreshes its library every three years to avoid degradation issues).

See also: Dropbox Bets the Farm on Shingled Magnetic Storage

Warner Bros. CTO Vicky Colf said: “That had always been our beacon of hope for what we believed would be possible one day, so when we learned that Microsoft had developed this glass-based technology, we wanted to prove it out.”

Warner Bros. is potentially looking at Project Silica to create a permanent physical asset to store important digital content and provide durable backup copies, Microsoft said: “Right now, for theatrical releases that are shot digitally, the company creates an archival third copy by converting it back to analog film. It splits the final footage into three color components —cyan, magenta and yellow — and transfers each onto black-and-white film negatives that won’t fade like color film.

Langston adds: “Those negatives are put into a cold storage archive. In these highly managed vaults, temperature and humidity are tightly controlled, and air sniffers look for signs of chemical decomposition that could signal problems. If they need the film back, they must reverse those complicated steps. That process is expensive, and there are only a handful of film labs left in the world that can do it.”

“We are not trying to build things that you put in your house or play movies from. We are building storage that operates at the cloud scale,” said Ant Rowstron, partner deputy lab director of Microsoft Research Cambridge in the United Kingdom, which collaborated with University of Southampton to develop Project Silica.

“One big thing we wanted to eliminate is this expensive cycle of moving and rewriting data to the next generation. We really want something you can put on the shelf for 50 or 100 or 1,000 years and forget about until you need it,” Rowstron said.

Project Silica: How Does it Work?

The technology builds on a breakthrough by the University of Southhampton.

Essentially, as a 2018 paper explains [pdf]: “When the beam from a femtosecond laser is focused inside a block of fused silica, a permanent small 3D nanostructure (which we will call a “voxel”) forms in the silica.

“In contrast to holographic storage, writing a voxel in glass involves inducing a permanent, long-term stable change to the physical structure of the fused silica material. Viewed from the top, the voxel has a grating structure (a nanograting) and is circular, with a diameter of approximately the wavelength of the light used to create it, and has a depth of a few microns into the glass.

“In contrast to conventional optical disc storage, many layers of voxels (i.e., over 100) can be written in glass, as the transmittance of fused silica is much larger than that of opaque thin films used in conventional optical discs, allowing light to penetrate much deeper into the material, for both writing and reading.”

By modulating the polarisation of the laser beam, energy, and the number of pulses, technicians can encode specific values into each voxel.

Top image: Microsoft senior optical scientist James Clegg loads a piece of glass into a system that uses optics and artificial intelligence to retrieve and read data stored on glass. Photo by Jonathan Banks for Microsoft.