Decades of conflict and war, natural disasters and insecurity have forced millions of people in Afghanistan to flee their homes. The country faces one of the world’s most severe internal displacement crises, and as of December 2020, there were more than 4.5 million displaced people in Afghanistan.

The Norwegian Refugee Council, an NGO with operations in over 30 countries across the world, was part of the relief effort for this crisis, but it lacked vital information it needed to direct its work. In 2018, the NRC partnered with UK-based geographic information systems (GIS) company Alcis to develop an AI-based system that could quickly and accurately assess how many people are living in camps in Afghanistan by counting the number of tents. Tech Monitor spoke with Tim Buckley, Alcis’s chief operating officer, to hear how the system was built and used.

In 2018, Afghanistan suffered one of the worst droughts in its history, decimating the year’s harvest. The resulting food crisis drove 300,000 people to flee their homes, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, with many families relocating to the cities in the north-west of the country. Refugee camps soon sprang up across Western Afghanistan.

In order to provide aid to these displaced people, the NRC needed to understand three things: how many were settling in the refugee camps; where they were coming from; and where it should seek to relocate them. But official data was lacking.

“Because it has undergone such movement and because the country has been so fragmented, accurate data that describes where people are just didn’t exist,” explains Buckley. “The data that was available nationally was based on a census that, I think, was done in 1979.”

Because it has undergone such movement and because the country has been so fragmented, accurate data that describes where people are just didn’t exist.

Interviewing people on the ground, meanwhile, would be a complex and resource-intensive operation. The unstable political landscape in Afghanistan means that geographical boundaries are always changing, so people refer to places in many different ways, Buckley adds. “You could have two people within the same village but they might call the village by different names.”

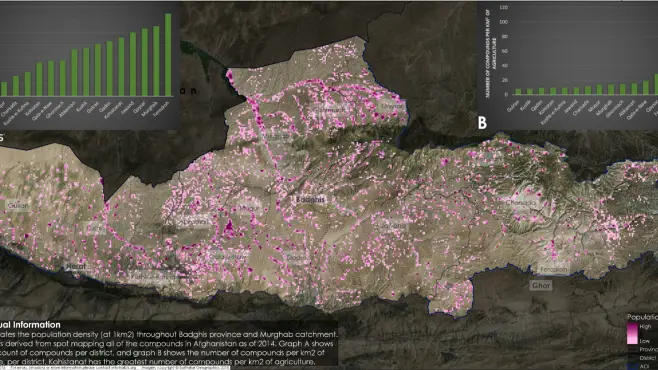

The NRC needed an affordable and accurate way to monitor the refugee crisis. It turned to Alcis, which has been collecting data and satellite imagery to track crop production in Afghanistan since 2004.

One approach would have been to count the tents that appear in the satellite images, which Alcis gathers from commercial sources, by hand. But this is “slow, repetitive, and frankly, it’s quite hard to keep operators focused if what they are doing is looking at a satellite image and spot-mapping tents,” Buckley says.

So automatically identifying tents in the satellite images was essential. Alcis’s first approach was to use the image recognition features of the geographic image software (GIS) it uses, which looks for pixels that are similar to those in pre-classified images. “We tried this approach and struggled quite a bit to get the accuracy we wanted,” Buckley recalls. “We were hitting around 75% of the tents being detected automatically.”

AI in action in Afghanistan

Alcis needed more advanced image recognition capabilities. One of the company’s staff at the time, Toyah Overton, was doing a machine learning PhD at London’s Brunel University. Buckley thought it would be a good opportunity to use her skills to build an algorithm that would accurately count tents. With TensorFlow, a free and open-source software library for machine learning, Overton developed a bespoke neural network to segment the image and count the tents. Applying deep learning meant the algorithm did not need to be trained with pre-classified data.

The resulting systems are far more effective – using Overton’s algorithm, Alcis could now automatically detect tents with up to 98% accuracy, and with minimal false positives.

Since the original algorithm was developed, Alcis has recreated its deep learning approach using ArcGIS software. “One of the big problems we had with the bespoke neural network was that all was done in a separate coding environment and getting data out of that and then the post-processing we’d have to do to get it geo-ready so it could then be used in the GIS for analysis,” says Buckley. “That was a major headache.”

Now, when it receives a new satellite image, Alcis feeds it through the system, segments and counts the tents and returns the data to the NRC. The location of the tents can be overlaid on to 3D model of the terrain, creating an explorable visualisation of the refugee camps.

The NRC has once again got in touch with Alcis to support it with the current crisis, as harsh weather conditions in the northern region of Afghanistan are again driving people from their homes. The withdrawal of US troops, and the political uncertainty that follows, are also likely to uproot communities.

“It looks like we’ll be providing similar support to the NRC through the summer and into the autumn and winter this year,” says Buckley. “The wider political situation is a massive cause for concern and I suspect there’ll be more displacement of people as a result of that.”