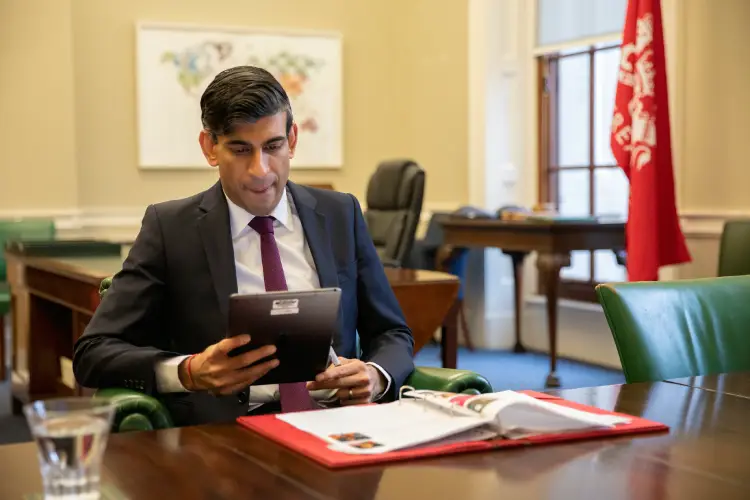

Tech is expected to be front and centre when Rishi Sunak unveils his budget later today, with investment due to be unveiled for “21st century” infrastructure and tech start-ups. These plans will join a growing chorus of pro-tech messaging from the UK government, which evidently sees the technology sector as a key pillar of post-Brexit Britain’s national identity and economic strategy. But each new plan serves as a reminder that it has still yet to announce a digital strategy that was due to be published last autumn.

Today’s budget will include £22bn in investment for the British Infrastructure Bank, a new initiative unveiled last year and due to launch in the spring, the government revealed at the weekend. “We are backing this bank with the finance it needs to deliver modern infrastructure fit for the 21st century and create jobs,” said Sunak.

The chancellor will also confirm the launch of an updated version of the Future Fund scheme specifically to help high-growth tech businesses or scale-ups. The Future Fund: Breakthrough will have a £375m budget to match private sector investment into tech companies raising £20m or more. Initially provided as a loan, the money can either be paid back by the company or converted into equity, meaning the taxpayer would have a stake in these businesses.

A Treasury spokesman told Tech Monitor the fund will “ensure the government continues to support highly innovative companies, such as those working in life sciences, quantum computing, or cleantech”. The original Future Fund was set up last year and provided matched funding to businesses in sectors that were struggling during the pandemic, and saw the government provide more than 1,000 loans worth more than £1bn, several of which have already been converted into equity.

The OECD defines scale-up companies as those enjoying more than 20% employee headcount growth and/or revenue growth per year. According to the data from the 2020 Scale-Up Report, produced last year by the ScaleUp Institute think tank, the most recently available data shows that the number of such companies is in decline, suggesting an intervention may be timely.

Investors welcomed news of the scheme, saying it has the potential to have a positive impact if managed correctly. Spyro Korsanos, managing partner at Fuse Venture Partners, which invests into a wide range of tech sectors, says scale-ups are an underserved area in the UK and Europe, with 40% of capital for such companies coming from the US.

But he adds: “Such investments require significant sector expertise. We believe that government co-investment should be made alongside [investment] funds with the skills to help companies to scale.” Conor O’Sullivan, vice-president at cybersecurity VC Paladin Capital Group, adds: “We are very happy to invest alongside government, with the proviso that the terms of the investment are market standard, commercially focused and work in the best interest of the company and all of its stakeholders.”

Tech start-ups are, unsurprisingly, also likely to welcome the chance of additional funding, according to Paul Hughes, an experienced start-up mentor and adviser, and chief operating officer at biotech start-up BIOS. He says any additional funding streams are “super positive”, but adds: “The original Future Fund was designed for a very specific purpose, which was not to let a whole bunch of companies die really quickly. The question for this one is whether it is really targeting the right kinds of businesses and is it really needed in the current environment?”

Hughes says UK businesses built on “solid” technology usually have no problems obtaining funding, and those which struggle either have fundamental problems with their tech or don’t have the potential investors are looking for. The numbers would appear to back this up; data from DealRoom shows UK tech firms attracted a record £11.2bn in VC investment last year, more than the rest of Europe combined. The government’s move could be a reaction to the increasing interest the EU is taking in tech start-ups, Hughes says.

“The EU is suddenly starting to make direct investments into start-ups, which has been absolutely banned for 40 years,” he adds. “So another question for me would be why we are doing this? Is it just a protectionist move to ensure companies don’t get brought out? Or is it to ensure we have the same funding opportunities as our European neighbours?”

[Keep up with Tech Monitor: Subscribe to our weekly newsletter]

The UK’s new data regime

Also this weekend, secretary of state for digital, culture, media and sport Oliver Dowden gave an indication of the government’s plans for its post-Brexit data protection regime. Writing in the Financial Times after the EU confirmed in a draft decision that it considers the UK’s data regime adequate, Dowden indicated that the UK’s emphasis will shift from privacy protection to economic growth.

Dowden said too many businesses are afraid to use data because “they don’t understand the rules or fear inadvertently breaking them”. This has “hampered innovation” and “prevented scientists from making new discoveries”, he said.

While reaffirming the government’s commitment to data protection standards that match or exceed the EU’s general data protection regulations (GDPR), Dowden said the UK can take advantage of global opportunities, claiming £11bn of UK service exports go unrealised due to “barriers with international data transfers”.

“By being more agile, the UK can capitalise on a multi-billion pound opportunity to boost trade in sectors where physical distance is no object,” he wrote.

The government plans to soon announce priority countries for its own data adequacy agreements, and with such enormous changes on the way, the identity of the next Information Commissioner could be central to the direction of the UK’s new data strategy.

The application process to succeed Elizabeth Denham, who is stepping down in October, opened on Sunday, and the position commands a salary of £200,000 a year. The new commissioner will be expected to “drive the responsible use of data across the economy, to build trust and confidence, and to communicate the wider benefits of data sharing for our society as well as for competition, innovation and growth,” according to the job advert.

Dowden’s column echoes comments made by Liz Truss, secretary of state for international trade, earlier this year. “We will promote modern rules that are relevant to people’s lives for digital and data trade,” she said. “We will also build an advanced network of trade deals, from the Americas to the Indo-Pacific, with the UK at its heart as a global services and technology hub.”

Where is the UK government digital strategy?

Bringing all these elements together should be the government’s new digital strategy, which was announced by Dowden in June and was due to be published last autumn. But the strategy, which will describe how the UK will transition to a digitally led economy and steps that will be taken to build a highly skilled digital workforce, has yet to emerge.

Questioned in December about when the strategy would arrive, Caroline Dinenage, minister of state for digital, culture, media and sport, told MPs “we are continuing to consider the best timeframe for delivering the strategy, in light of the broader national context including the Covid-19 pandemic”.

She added: “We are currently working towards publishing in 2021.” In the strategy’s continuing absence, Hughes says it would be wise for the new Future Fund to invest in companies that align with the UK industrial strategy priorities. Otherwise, he adds, “if we’re not careful, we’ll start to get a bit of a hodgepodge of different initiatives providing different kinds of funding for different sectors”.