Cynthia Bahati has just quit her job.

In some ways, it feels inevitable. Interested in where technology meets art since her days studying computer science at UT Austin, Bahati is an evangelist for non-fungible tokens (NFTs), and the potential they have to brighten the futures of thousands of struggling artists. During the pandemic, she became a creator and collector of NFTs, minting her first – a voice note – in February. “It was just audio of me talking, in the same way I’m talking to you now,” she recalls. It sold immediately.

“Eventually, I started liking the NFT stuff more than I liked [my] actual job,” says Bahati, who began pursuing the acquisition of new tokens on a freelance basis. Eventually, she encountered an NFT poem minted by rap artist Latashá Alcindor. “It’s a rare piece to have, a musician performing poetry,” says Bahati. “I knew I wanted to get it, but I knew I couldn’t afford it. So, I thought…that maybe we could make a DAO.”

What is a DAO?

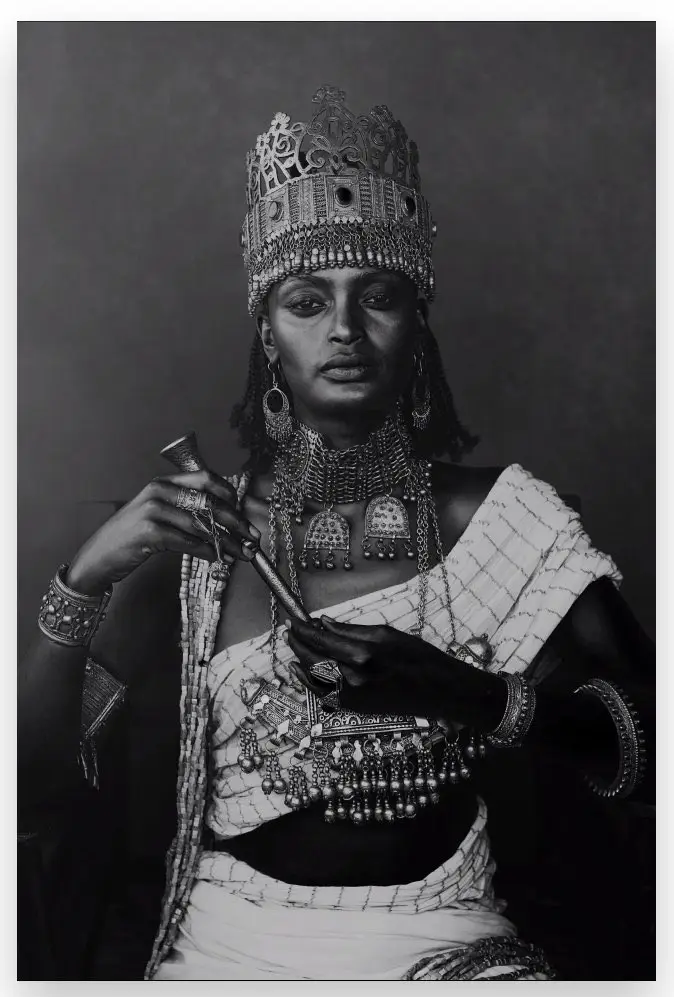

A DAO, or a distributed autonomous organisation, is a group where decisions are made collectively in votes among individual members. Located on a blockchain, its procedures are automated by smart contracts and completely transparent to the outside world. This eliminates the need for third parties to arbitrate decision making, proponents say, fostering trust within the group and making DAOs an ideal organisational tool for pooling and investing funds. Bahati decided to name hers ‘herstoryDAO,’ with the goal of empowering black female and non-binary NFT artists. “That decision was made in 20 minutes, to start the DAO, to name it, to get it started,” she says. “I had no idea about the logistical implications.”

It took a fortnight of frantically coding herstoryDAO’s underlying framework in her spare time that convinced Bahati to devote her full attention to the organisation. Despite several setbacks, she has remained irrepressibly enthusiastic about the DAO’s potential: “It’s kind of exciting to be at the cusp of so much change and evolution that I just couldn’t say no to the opportunity to do it full time.”

Bahati isn’t alone. In recent years, DAOs have grown from being niche propositions at the fringes of the crypto scene into venture capital funds valued at hundreds of millions of dollars. And they continue to proliferate. As well as DAOs that buy and sell NFTs, there are DAOs that aim to transform publishing, a DAO that forms the basis of an online game, and even one for e-residents of Estonia. Advocates of the model say it has the potential to spread even further, helping to transform conventional corporate governance into something wholly transparent and, ultimately, more democratic.

Even so, questions remain about the governance of DAOs, and how they can function effectively when their membership grows into the hundreds or thousands. And hanging over all of them is the example of ‘The DAO,’ a crypto investment from which $50m worth of Ether was stolen in 2016 in one the biggest cybercrimes of all time. Its collapse arguably set adoption of the model back by several years, and continually prompts critics to ask whether the future of DAOs is one of democratic transformation, or a utopian experiment destined to end in tears.

Philosophy of the DAO

José Nuno Sousa Pinto is firmly in the former camp. “This is the future of corporations,” says the chief legal officer of Aragon, an association that provides DAO developers with an underlying platform from which to build their organisation. “What we are looking at is a different type of governance structure, a tool that allows the organisation and governance of thousands of members in different jurisdictions in a completely decentralised form, in the most transparent, immutable, fair process possible.”

The system of collective leadership inherent to DAOs, in theory, fosters a sense of inclusion and investment among the membership in the organisation’s future. The blockchain underpinning each DAO means that “when you vote in a DAO, your vote is registered and it’s immutable,” says Sousa Pinto. “Everybody can check and validate the decision taken within that process,” encouraging a culture of public accountability among individual members.

Encoding the DAO’s rules in smart contracts also allows for decisions to be made without recourse to the legal bureaucracy that typically accompanies the process in the real world. However, “once the rules are set, the rules are set,” says Daryl Hok, chief operating officer at CertiK. Any changes in the smart contracts governing the DAO are usually put to the membership in a vote, which means that it can take longer for such organisations to adapt to changing governance or security circumstances.

This isn’t to say that the DAO model cannot be adapted from the outset to suit the overall purpose of the organisation. While decision-making in a pure DAO – where every member has a single vote – has the potential to become sclerotic if the organisation’s membership approaches a certain size, there is nothing to stop its founders from apportioning multiple votes, or ‘governance tokens,’ to members according to certain criteria: the length of time they’ve spent on the DAO, for example.

Another solution to governance bloat is to ‘shard’ the DAO, creating a miniature version of the core organisation in the same way a company would start a new department. “I feel this idea of fractionalisation within the DAO is going to become quite popular,” says Bahati. Indeed, it’s integral to herstoryDAO’s plans for future expansion, with Bahati envisioning individual DAOs responsible for collecting NFT photography, music and fashion items.

There’s also nothing to stop an organisation or a company ‘DAO-ifying’ parts of its own operations, imposing the structure on certain teams or departments while retaining traditional methods of decision-making at the top. This process is already underway at the Aragon Project. Governance-token holders “will be able to vote on any matter that is relevant to the association,” says Sousa Pinto, in addition to already using different DAOs to manage funds.

Power dynamics in DAOs

While the transparency built into the DAO model may prove a draw to individuals disenchanted with opaque corporations in the real world, it “doesn’t necessarily mean that the decisions will be made properly and accurately”, says Hok. Nor does it mean that power within the DAO will be shared equitably. For example, there is nothing to stop the founders of a DAO from hoarding governance tokens and rewarding themselves with a controlling stake in the decision-making process.

User engagement is also an important determinant of a DAO’s success. Jackson Dame has witnessed this first-hand as a member of Mirror, which intends to revolutionise publishing by leveraging the DAO model to the advantage of writers. On Mirror, voting shares are allocated according to user participation. Many choose to increase their number of governance tokens by taking part in a competition on the DAO called the ‘$WRITE Race,’ where members debate who should win a new Mirror domain that can then be used to start a new affiliated publication.

Dame won the race last month. The overall experience left him hopeful about the potential of the DAO model, and he predicts the domain he won will form a central part of his own creative process. Some winners seem less sure. “I noticed that a lot of people were just trying to get on the platform because it seemed really interesting and cool, but they didn’t really have any sense of how they were actually going to use the platform,” he says. Others, meanwhile, just used the $WRITE Race as an opportunity to advertise their own cryptocurrency start-ups.

It shouldn’t be surprising that not all members of a DAO will remain completely engaged in its operations, even if the voting share is determined by enthusiasm. Another solution to the problem could be for members to appoint proxies to vote for them. To what extent, then, are DAOs really any different from conventional corporate hierarchies? Sousa Pinto concedes that they are similar in some respects. “But that doesn’t mean you’re just following the rules from traditional and conventional corporations,” he adds. Fundamentally, “there is a simplification of process, and of bureaucracy.”

There is a difference in ethos, too, according to advocates. Currently, founding a DAO means buying into a culture of collegiality, one that is setting democratic precedents for the wider sector. For his part, Hok predicts that the sector will see more ‘fair launches,’ where founders deliberately refrain from giving themselves a majority of governance tokens. When that happens, he says, “I think things will just lean toward the direction of true democracy.”

DAOism

Democracies, however, can be undermined. In 2016, the collapse of ‘The DAO’ was caused by a hacker’s manipulation of the organisation’s smart contracts, allowing them to drain it of almost half its funds. Users eventually got their money back after developers rewrote the DAO’s underlying code to make it as if the hack never happened, but not without forking the entire Ethereum blockchain and casting doubt on the integrity of the DAO model for several years.

Has the sector now learned its lessons about security? “In 2016, it was just so much earlier,” says Hok, a time when the blockchain was still in its experimental stages and code that wasn’t as robust as it is today. Nowadays, developers are generally “more conscious about security as an issue”.

Even so, new problems are being encountered every day. For one thing, many DAOs lack legal protections. “Without…an internal agreement between the members of that DAO, in many jurisdictions that type of organisation is understood as a general partnership,” says Sousa Pinto. This means that “every member of the DAO is responsible not only financially, but also on the liability level, not only for his actions but also the actions of other members of the DAO.”

While that might put off all but the brave from joining their local DAO, certain jurisdictions have begun to amend legislation to allow these organisations to be viewed as a single legal entity. In Wyoming, for example, new legislation will soon permit DAOs to be incorporated as limited liability companies. In Switzerland, meanwhile, legal recognition may be found in the form of an association, or a verein, which can “also, at the same time, confer some certainty and some protections to the DAO members,” says Sousa Pinto.

There are also technological barriers to entry, says Bahati. For one thing, most of the NFT arts market is concentrated on the Ethereum network. That’s great for security, says Bahati, but the ‘gas fees’ required to successfully make a transaction mean that hosting a DAO on the platform increases the cost of membership. Bahati has also experienced compatibility problems between the security protocols underpinning DAOs and NFTs, which has sometimes led to them temporarily disappearing after purchase. “The NFT just wasn’t showing up on our end, and that scared the living crap out of me,” she says.

Other aspects of the model remain untested. Hok posits a scenario where, after a crash in the value of a cryptocurrency takes place and governance tokens can be bought cheaply, a DAO could experience a hostile takeover. This isn’t necessarily a barrier to wider adoption, though, and Hok believes that the fundamental appeal of the DAO model – a transparent and secure way to enable collective decision-making – could see them break out of the crypto space in the near term. “I think non-profits would be the closest direction of what’s realistic,” says Hok. In turn, this has profound implications for how trade unions and industry associations are organised and managed.

The co-founder of herstoryDAO, too, remains doggedly optimistic. “We’ve been marginalised voices in this space and in history,” says Bahati. For its members, herstoryDAO is an opportunity to help reverse that and do it within a model that feels almost ancestral. “The best analogy for a DAO would be a tribe. And it feels very communal. It feels very ancient.”