Joe Biden has pledged to ensure the future is “made in all of America” during his presidency, with a package of measures designed to enhance the country’s manufacturing capabilities. This could prove to be a welcome boost for US chipmakers, who have long dominated the semiconductor industry but are losing ground to competitors from around the globe.

On the campaign trail, Biden said he would invest $300bn in America’s research efforts, as well as introducing a programme of incentives, new financing options for manufacturers and putting $400bn into a “Buy American” procurement fund. “Smart investments in manufacturing and technology” will give US workers and companies “the tools they need to compete” with competitors from around the world, the president-elect’s campaign website states. US chipmakers will be among those waiting to see if he can make good on his promises.

The US semiconductor sector: dominant but in decline

Companies such as Intel, AMD and NVIDIA have helped the US dominate the semiconductor market for decades, and it is still way out in front of other countries when it comes to chip revenue, accounting for 47% of the market in 2019.

However, all is not as rosy as it appears. “The United States does continue to lead in semiconductor design and R&D,” says Stephen Ezell, vice-president for global innovation policy at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) think tank, who has penned several reports on the state of the global chip market. “However, what is apparent is that the US share of value-add in the global semiconductor supply chain, as well as the share of production of semiconductor chips themselves, has actually fallen quite substantially over the past 15 years.”

Indeed, Ezell’s research shows that, taking into account the value added at all stages of the chip supply chain, the US share of the market fell from 28% to 22% between 2001 and 2016. In the same time period, China grew its share of global semiconductor value-add from eight to 31%. Ezell attributes this decline in part to what he describes as “unfair tactics” employed by China, such as IP theft and heavy state subsidisation of the industry, as well as the evolution of business models in the sector and the success of fabless processors, where designers come up with the IP but get their chips produced in the Far East where costs are lower.

Ezell says that when it comes to semiconductor manufacturing, domestic policy has also been a hindrance, with capital investment declining, tax policies that have deterred investors and stiff competition from other nations offering greater incentives. “There is a fight for every factory in the world being developed today,” he says. “Tending to our own environment here in the US, to make sure that we provide an attractive and compelling offer for manufacturing companies, is something we need to do a better job of.”

Biden’s semiconductor policy: CHIPS with everything

The Biden administration is likely to lend its support to legislation first introduced during Donald Trump’s presidency designed to give an uplift to American chipmakers. The Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America act and the American Foundries Act were both designed to bolster the US semiconductor sector, and have been rolled into a larger piece of legislation, the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). This passed both of the House of Representatives and the Senate last year, and is now in the committee stage where negotiations will take place over budget.

The act calls for significant investment in the sector. It suggests that up to $15bn in state subsidies and incentives is needed to attract new chip-manufacturing plants to the US, and that $12bn should be allocated to government research agencies to fund semiconductor R&D. Should it be granted, this funding could be the catalyst for the construction of a wave of new American semiconductor fabrication plants (fabs), with the Taiwanese Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) ready to take full advantage.

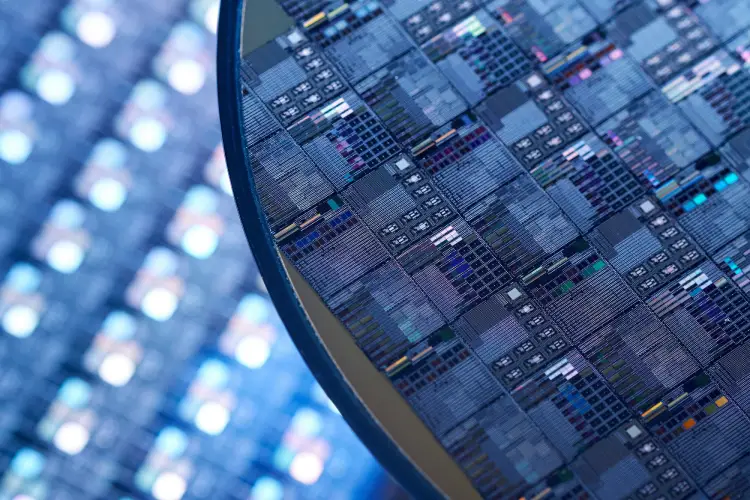

TSMC, the world’s leading chip manufacturer, already has plans for a new $12bn fab in Arizona. Scheduled to open in 2024, it will be capable of producing 20,000 silicon wafers a month and be ready to build the next generation of 5nm (nanometre) chips, offering improved performance and greater energy efficiency.

Already serving major fabless US chipmakers such as AMD and NVIDIA, TSMC is in pole position to enjoy a renewed focus on semiconductor manufacturing from the White House. Meanwhile, Intel, the largest chipmaker in the US, has encountered difficulties with its in-house manufacturing process and is considering outsourcing production to a third party.

TSMC and other global businesses stand to gain as much from fresh US investment in semiconductor manufacturing and R&D as home-grown businesses such as Intel or AMD, says Antonio Varas, managing partner in the telecoms, media and technology division at Boston Consulting Group (BCG).

“As far as we understand it, the goal of these policies is to ensure there’s a more globally diversified semiconductor value chain,” he says. “That means making sure you have manufacturing capacity located outside of East Asia.”

Biden’s semiconductor policy, and any investment via the NDAA, is likely to first benefit chip foundry companies such as TSMC, Intel and GlobalFoundries, Varas says. Integrated design and manufacturing businesses like Micron Technology and Texas Instruments could also be boosted, with incentives designed to benefit both aspects of the market.

Biden and China

Semiconductors were one of many fronts in the ‘silicon cold war’ with China that came into focus during the Trump presidency, with US companies banned from doing business with the likes of Huawei unless given a special licence by the US government. Intel was among those to be granted a licence, but the restrictions hit revenues for many chipmaking companies.

Biden is widely reported to have picked Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo as his commerce secretary, and the appointment of the former venture capitalist could signal a slight softening of relations with China. In a speech she gave at an event in 2017, Raimondo reportedly expressed her hope that the US could broaden its co-operation with Beijing.

But BCG’s Raj Varadarajan says the trend of increased friction between the US and China is likely to continue under Biden’s leadership, with key figures from across the political spectrum united on the approach required around the main issues.

“There’s bipartisan agreement on cybersecurity, intellectual property protection and country competitiveness, and semiconductors are very much at the core of all these issues,” he says. “The tone of talks around tariffs might change, the substance of discussion [between the US and China] is really around these three issues, and a lot of that focus will remain until solutions are identified.”

Varas adds that the wider “palette of responses” available to Biden is likely to be one of the main differences when he takes office. “Trump’s approach was an almost all-out confrontation framed in ideological terms, so there was no chance of finding common ground,” he explains. “[Biden] is likely to take a more multilateral approach, engaging allies, forming coalitions and treating each issue separately on a case-by-case basis rather than taking bilateral action.”