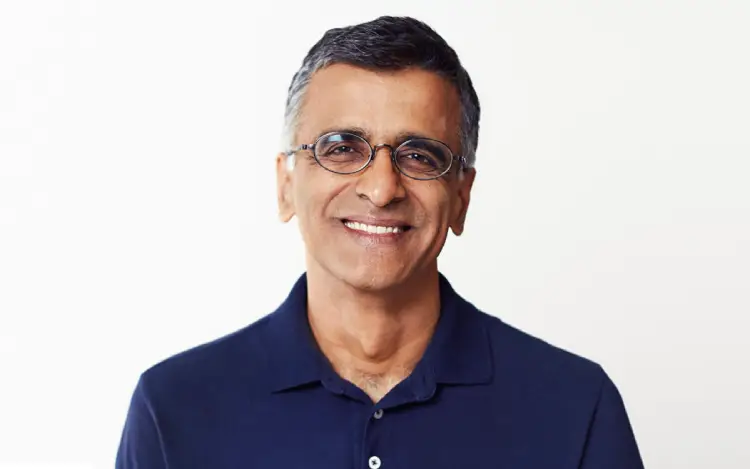

“It’s not wrong to be big and successful,” says Sridhar Ramaswamy, founder of search start-up Neeva. “It is, however, not right to use that power to squelch competition.”

The former head of Google’s $115bn advertising wing, Ramaswamy is now competing against his old employer in a market it dominates. That dominance has attracted the first antitrust case brought by the US Department of Justice against Big Tech since its 2001 suit against Microsoft.

The case focuses on Google’s search business, in particular its agreements with Apple and Android device manufacturers, and browser makers including Mozilla, to make Google the default search engine.

While some have sought to downplay the importance of the case, Ramaswamy says it could be seismic for the search market and the chances of challenger search engines like Neeva succeeding.

The DOJ is “focused on distribution channels and defaults which I think gets to the heart of the matter,” says Ramaswamy. “One of the things that a lot of tech companies do is they set up defaults and then tell the rest of the world that users have options – competition is just a click away… but most people never change their default, unless that is actively placed in front of them.”

Some analysts shrug off the idea that prohibiting Google’s agreements with device and browser-makers would have any material benefit to other search engines, but Ramaswamy disagrees. “I would say that defaults, as I know from personal experience at Google and elsewhere, play a very large role in what users and customers end up doing.”

Therefore, Ramaswamy says he believes the DOJ’s focus on defaults is “needed and important”.

For Ramaswamy, the ideal result would resemble the outcome of the Microsoft case: users should be given a choice when they first set up a device about what search engine they want to use, he believes.

But how to implement this choice is still debated. As a result of an anti-competition case against Google in Europe, Android users in the region are now offered an alternative to its search engine, but Google’s competitors say that the intervention isn’t working.

The choice of options that users are given is based on an auction by Google, with the companies that pay the highest winning a spot. This has negatively impacted smaller, not-for-profit and regional search engines, such as DuckDuckGo. “Ideally, this choice should not involve everybody having to pay money,” says Ramaswamy.

Google rivals recently wrote a letter to the EU commission arguing Google’s solution should be ditched in favour of a more collaboratively designed choice screen favouring an unpaid model that has space for more competitors (at present Google only allows three in addition to its own search engine). While the current model has allowed larger competitors such as Bing to gain more slots, Google still holds a market share of more than 90% in Europe.

“Part of my reason for starting Neeva was I did not want this very important function to become a monoculture,” says Ramaswamy. “It’s like having a single radio station that tells you what you should listen to on a single TV station. We benefit from a plurality of opinions and voices and I think search engines are certainly one of our most important gateways to information.”

In Neeva’s model, users pay to avoid ads and tracking. “I felt that the ad model… was only going to get worse, it was going to get in the way of Google search continuing to be a great product,” says Ramaswamy. “One tries to look forward into the next few years and an easy prediction that I can make is that Google five years from now is going to have more ads, not less ads.”

That Google’s monopoly on search has degraded user experience on the dimension of privacy is one of the central pillars of the DOJ’s case. Antitrust scholar John Lopatka told Tech Monitor that this charge could be difficult to prove, because the DoOJ will have to show that customers care enough about privacy to have suffered from Google’s monopoly.

Ramaswamy, as well as other relative newcomer DuckDuckGo, are betting that people do care enough about privacy. Ramaswamy says that Neeva got a huge amount of attention when it launched, with tens of thousands of people signing up to take a survey to offer opinions and feedback. This has made him confident the company will be able to attract its first wave of customers organically.

He says the company is having ongoing conversations with browsers such as Firefox and Brave, but are taking things “one step at a time”.